Three years ago, Danna Gonzalez barely cared about graduating from high school. “Good grades weren’t my priority because I didn't think I was going to go off to college,” she says. But earlier this month, the petite, long-haired daughter of a truck driver not only graduated, she did so glowing with the knowledge that she was college-bound. “I’m so excited because I can actually do something with life, like get an education. I can actually be what I want to become.” She crossed the stage in cap and gown, grasping not just a diploma but four community scholarships, including one from Puente, which she will apply toward her college education.

Gonzales also got a class award for community service, which includes her many hours of service as a Puente volunteer. Prior to graduation, she received seven other school awards for all the hard work she did to turn her grades around and pass her classes.

The 18-year-old says she’s become a different person since she applied for a DACA permit three years ago. (DACA stands for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a federal initiative that since 2012 has awarded work permits to roughly 100,000 previously undocumented residents who were brought to the U.S. as children.) Although DACA is not a path to citizenship, it awards qualified applicants a legitimate Social Security number and ID papers that can be used to apply for a driver’s license and find work. (California subsequently passed a law, AB60, which makes driver’s licenses available to all Californians regardless of their immigration status). In California and a few other states, DACA also qualifies students for certain kinds of college financial aid.

The results are often transformative: in a 2014 study of DACA recipients, a majority of those surveyed were able to get a new job, open their first bank account and obtain a driver’s license.

Danna Gonzalez, Ana Barron and Yessenia Perez are three of 23 local youth who have received their work authorization since Puente started processing DACA applications for free in 2012. That little piece of paper marked a milestone for many youth in the South Coast community. Three years on, 13 of them have already renewed the two-year permit for another two years. They are looking ahead to exciting fields of study and full-fledged careers they never allowed themselves to dream of.

In Gonzalez’s case, that dream entails attending Cabrillo Community College in Santa Cruz, where she will debut as a student this fall. Following two years of prerequisites, she will enter a training program to become a dental hygienist. “I’m excited but I’m scared,” she admits with a laugh. “In Pescadero it’s a small school, so we have a lot of support from the teachers. At Cabrillo, they won’t care if I attend school or not.”

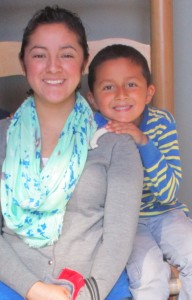

Ana Barron is still adjusting to life as a student at Foothill College in Los Altos Hills, a campus she never thought she would set foot on. The fresh-faced nursing student easily fits in among her community college peers, who might never guess she’s 26 and has a 6-year-old at home.

Barron came to the U.S. from Mexico at 14, and had her son, Maximiliano, at 19. For most DACA recipients, having work authorization mainly affects one person’s future – their own. For Barron, DACA ensures, at least temporarily, that she is guaranteed a reprieve from ever being deported to Mexico and separated from her American-born son. It also means she can work toward a degree that will help her get a high-paying job, lifting the prospects of her small family.

Barron enrolled at Foothill with her heart set on entering the medical field – she’ll choose between nursing, radiology or respiratory therapy, although nursing is her top choice. “I like talking to people and helping them,” she says, simply. As a part time student and a full-time mom who also works as a waitress in Pescadero, Barron knows it’s going to take her several years to get enough credits to transfer to San Jose State and complete her degree. It’s complicated and expensive. “But as long as I feel good about it and don’t give up, I think I can do it,” she says.

Barron loved high school, but her pregnancy prevented her from going to college. After her son was born, there didn’t seem to be much of a point – until she got a personal phone call from Rita Mancera, Deputy Executive Director of Puente, inviting her to apply for DACA. Suddenly she saw a future for herself outside of her waitress job. “It’s wonderful to be able to move from one place to another without worry,” she says today. “It’s a good beginning, because more of the programs will probably ask me for a Social Security number later on when I try to apply.”

Barron’s unique situation as a parent who happens to qualify for DACA also makes a strong case for DAPA, Presient Obama’s Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, an executive order providing temporary protection from deportation and a work permit. The program is in limbo as the federal government readies for a legal showdown, and so are hundreds of Pescadero residents who might benefit. Puente has spent considerable staff time and resources moving forward to prepare for DAPA, and recently received Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) agency recognition, which will allow staff to process most DAPA applications in-house.

“We know children whose parents do not have work authorization. They’re always on edge,” says Mancera. “When parents have a work permit, they aren’t worried about their jobs. If they get their hours cut back, they can apply somewhere else as well.”

Children without papers also experience fear, insecurity and a sense of self-rejection; Mancera sees it all the time.

Generous funding for Puente’s DACA efforts comes from the Grove Foundation of Los Altos, and the foundation’s support has been changing lives.

“When the youth are in school, I see an immediate difference. There are more doors open in their academic futures,” says Mancera. “For people who are out of school already, the work opportunities suddenly just change.”

That was never truer than for Yessenia Perez. She is studying for a teaching credential but already has a job she adores, working at a daycare where she cares for 1-year-olds. The confident 23-year-old married her college sweetheart last month and moved to Redwood City from Pescadero. After several years of staffing Puente’s children's programs, and then working as a teacher’s aide at Pescadero Elementary, Perez knew she wanted to work with young children.

When DACA came along, Perez was literally first in line at Puente with her documents in order, ready to apply. “I knew DACA was going to change my life. That it was going to help me to have my driver’s license instead of waiting for rides from friends,” she says today. “Later on I realized I could get the job that I wanted in the place that I wanted.”

But she didn’t know it would happen so quickly. A friend working at a private daycare and preschool in San Mateo recommended Perez for a post there. She applied for the job, but went to the first interview with some trepidation – she knew she’d have to explain that she only had a 2-year work permit, and that the interview process would probably be a slog. Instead, she was hired on the spot.

“I thought, thank god I have the DACA permit. If I didn't have that, it would have held me back,” she says.

Three years into her stint at Cañada College, Perez has earned a certificate in early childhood development and is halfway toward her goal of an associate degree. Eventually she will transfer to a four-year college and enter a teaching program.

One of the biggest pleasures of Perez’s job is the fact that she can be honest with her employers about her work status. “At the beginning, I was waiting for them to ask me questions,” she says. But it turns out they were more interested in her skills. “They were fine with it. They even said, ‘If you ever need a letter from us just let us know.’ I was amazed.”